“Learn how to see. Realize that everything connects to everything else.”

I photograph as a spiritual practice. It’s a spiritual practice for two reasons. First and foremost, photography is the healing of what I wrote about in last week’s blog — my old belief, fear and sadness about not being able to be an artist. I have photographed my whole life, yet I never have thought of myself as a photographer. I lived with a photographer for ten years, and as the driver on so many photo journeys I was given the opportunity to look, to see my surroundings more deeply. I took pictures of so many places in my mind. But when I photographed, it was only for myself in small, unadventurous, safe ways.

It wasn’t until the advent of the iPhone, which brought a new casualness both to taking and sharing photos, that I began to think differently about photography. Other people seemed to have so much ease and find such joy in their pictures — which were mostly of family or food or travels — things that brought pleasure or made them feel connected. I took courage from them and began to think about sharing the joy I found in mine.

The task was getting that critical voice out of my head and showing up to that enjoyment of just seeing. So, I would try to photograph without thinking and then look at the pictures later to find out what I had seen. That twofold process taught me a lot about what interested me and how I saw the world. I loved it so much that it has become an almost daily practice. To photograph, whether with my cameras or iPhone, and then come back later to “see” what I “saw”.

The next step was sharing them. When I discovered Instagram, something eased in me. I have been an art dealer, publicly and privately for over two decades. Although I have had the privilege of showing the work of many amazing artists, I have to admit that my greatest joy was creating a small space dedicated to showing the work of people who had never had a gallery show. Like so many things in this world, there is a discouraging Catch-22 in the art world. No matter how good you are as an artist, people want to know “where you have shown” in order to give you a show. Even if I was not the right permanent dealer for an emerging artist, I gave them that “first show”. Having grown up in such privilege and having been given so many legs up simply by virtue of my lineage, that was my way of paying it forward. What I didn’t know was how joy it would bring me. That’s what Instagram was for me — my own little self-created gallery space. It didn’t matter if three people “followed” me. I felt safe to share my pictures there.

Lately, people have commented on how much better my pictures have been getting — even telling me that I have a “good eye”. That made me realize that the less I have censored or critiqued myself, the more I have just enjoyed the process, and so the “better” my eye has gotten. Which makes me realize that better happens in a variety of ways: Practice of course. My eye now sees what makes my heart sing as a way of prompting the singing. I love that! But also Joy. I photograph for the joy of it. And that has changed everything.

Some people would say I have always had a good eye. But if I’m honest, the things that I see “best” have always been the things I love the most. Take Navajo textiles, for example. I ADORE Navajo textiles — and my love managed to manifest immense beauty in my life. When I was one of the top Navajo textile dealers in the world, people from all over the world would call me and say, “I’ve got a great Victoria blanket.” I loved that. It meant I was sharing the beauty I saw with them without words.

Perhaps the best examples of this were my biannual gallery photo shoots. I had the idea of using my dog Jackson in my advertising. What none of us knew was how much he and I and everyone else would come to love those sessions. I can't tell you how many times we would set up the whole scene and he would place himself in within them in a far better way that we had imagined. He loved his job. I loved him. We loved the whole experience. With Pure Love at the center of every scene, everything couldn't help but come together. Those images became iconic (thanks to Eric Swanson and Cyndy Tanner) because the heart and soul of those images was my beautiful beautiful four-legged companion.

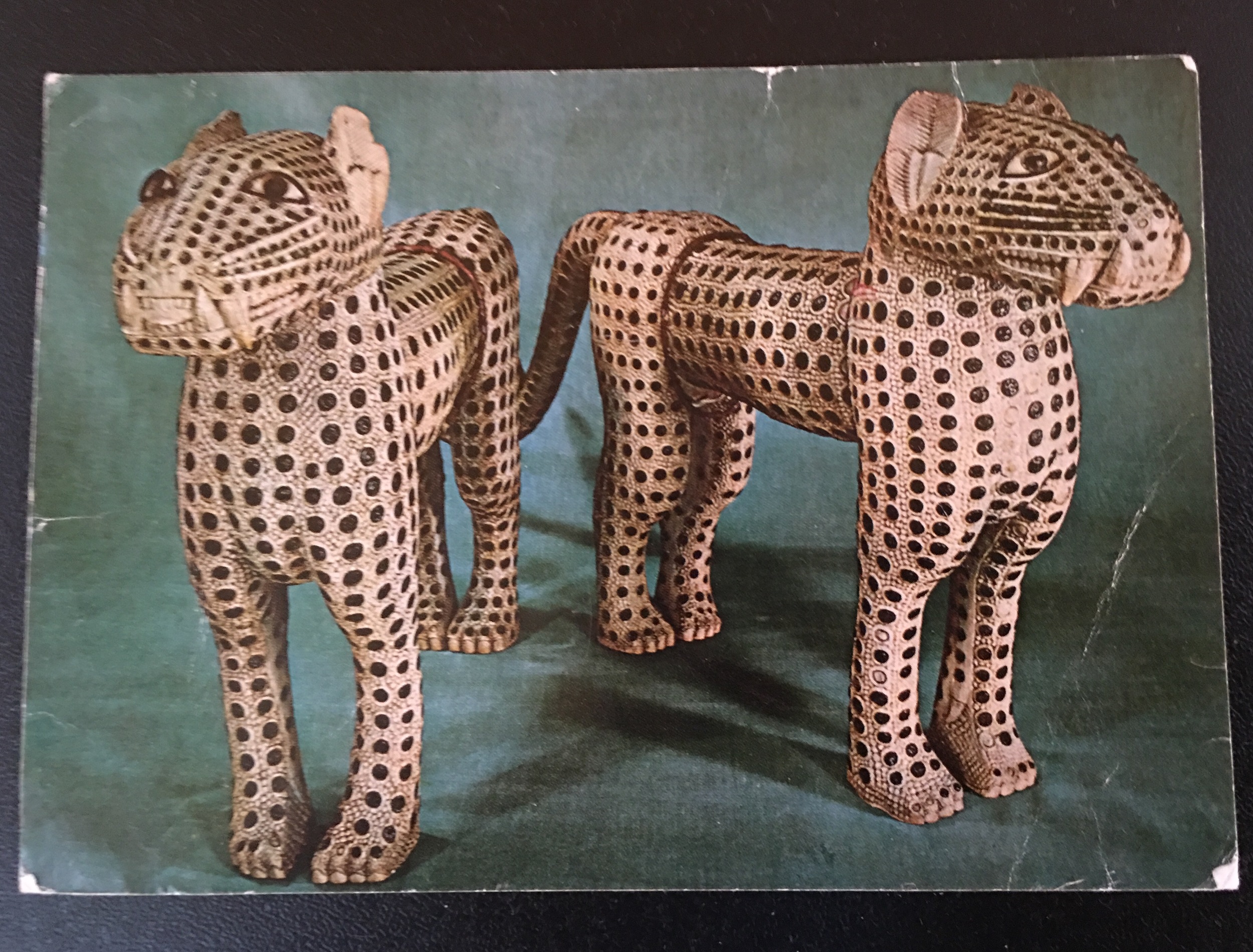

In October I will have the first show of my photographs. It makes me nervous to even say that. So I’ve decided to think of the pictures that will be in this show as my postcards from the road. My dad always sent postcards when he traveled— to me, to my mom and my brother, to other family members, to friends, to fans, to anyone and everyone. It was his way of feeling connected from far-flung places. Those postcards were how I learned about the world.

My parents hung a map over my bed in which they placed four pins with colored flags — one each for my father, my mother, my brother, and me. Blue, green, red, and yellow. Whenever I received a postcard from one of them, I found the place on the map and I moved the pin. When I was a kid, frankly it was the names of the places more than the pictures on the cards that intrigued me. I loved the funny or exotic names: Kalamazoo, Chattanooga, Timbuktu. Names that were fun to pronounce. And I loved watching the pins move from place to place and imagining such a big world. When I finally got to KalamazOO last fall, I was elated. I felt like I had fulfilled part of my life’s pilgrimage. Next February, I will finally get to ChattanOOga. Yipppeeee! It’s almost like I’m still moving my own yellow-flagged pin on the imaginary map that still lives in my mind.

The title of my October show is Learning to See: Postcards from the Road, 2011 - 2016. It was when I began changing my life in 2011 that I began photographing again. That is also when I began learning to see anew. A Course in Miracles tells us that what we experience in our lives is really a projection of what we/society believe/s. When we see the events, experiences and even the other individuals we encounter in our lives as “screens” onto which/whom we project the hidden parts of us that need healing, we can approach any situation from the desire for healing. Relationships are among our most intense and important ways of doing this -- by allowing us to see our untouched dark places in order to expose them to the Light of healing. When we understand this, we can resist the urge to blame or judge others and instead heal that which feels separate, ashamed, guilty, angry, hurt, separate in ourselves.

To do this, we have to recognize that whatever is happening out there really is our own interior movie writ large on the screens of our lives and of other people. In that sense, anything that allows us to screen out our subconscious is vital. It is the way we change our channel from fear to Love. For so many of us, creativity is one of our chief ways of doing this. We write, paint, sing, act, dance, sculpt, play, build, cook, sew, craft ourselves whole. The creative act is an act of healing — but not just for ourselves, but for the world.

This was what I learned from my father — for whom museums were his church and art the chief tenets of his faith in humanity. He believed that if we, as a species, could continue to create, we resist our impetus to destroy. He and my mother taught me the importance of beauty. But the first time I understood the call of beauty in my own life came about while studying art history in college. Although I was intellectually drawn to very dark and intense artists and movements, I would find myself in museums almost furtively standing for hours in front of beautiful paintings, as though they were a guilty pleasure. But those beautiful paintings are the ones that have remained the art to which I still make regular pilgrimages, which still crack my heart open and make my soul sing. It just took me a long time to give myself permission to allow myself to revel in that necessary Beauty.

Both John Berger and John O’Donohue have been my continuing guides in that reverence. Berger believed. “That we find a crystal or a poppy beautiful means that we are less alone, that we are more deeply inserted into existence than the course of a single life would lead us to believe.” Similarly O’Donohue feels that, "When we experience the Beautiful, there is a sense of homecoming. . .We feel most alive in the presence of the Beautiful for it meets the needs of our soul.” In fact, O’Donohue goes so far as to aver that “all the contemporary crises can be reduced to a crisis about the nature of beauty.”

Beauty, both men agree, is very different that the illusory seduction of glamour. When I was in my early twenties, someone told me that the original meaning of the the word glamour was — a spell. How true! And that, of course, is why, as O'Donohue so cleverly puts it, "No one every catches up to glamour." Berger wrote, “Glamour cannot exist without personal social envy being a common and widespread emotion.” While O’Donohue warns that to mistake glamour for beauty is to invest in a “highly fickle and commercially driven enterprise that contributes to the humdrum. . . Glamour. . .has but a single flicker. In contrast, the Beautiful offers us an invitation to order, coherence, and unity. When these needs are met, the soul feels at home in the world.”

John O’Donohue goes so far as to believe that it is the destruction of beauty on our planet that has set the stage for so much of the destruction we witness every day — on the news, on our own streets. Without the soul-soothing solace of beauty, we have eroded our trust in the future. He recognized that it might sound completely naive to many that this is the time to “invoke and awaken beauty”. But he did, writing: “There is nowhere else to turn and we are desperate. . . it is because we have so disastrously neglected the Beautiful that we now find ourselves in such terrible crisis.”

If indeed, the world we experience is the projection of our inner lives, we have to reclaim the Beautiful within is to manifest it without. To say no to the violence, the ugliness, the hatred, the fear in our own psyches and to love ourselves and the world back whole.

When I set myself the assignment of brevity last week — writing one paragraph about my three favorite photographs of the past five years — little did I imagine that it would prompt such a profound continuing conversation with myself about Beauty. But in fact, when I lost the belief that I could create art, I lost a part of my soul — and that has mirrored out into my life in ways that have hindered the healing of myself and of others. (Yes, I am failing at the brevity part. But I’m having a wonderful time doing it!)

To share these photos then is to share my soul — by sharing not just what I saw, but what these photos taught me I saw, and how they have taught me to see more deeply, more truly, more lovingly, more hopefully. And, frankly, during a week in which the global violence continues to escalate in a way that is so deeply dis-heart-eking, writing about the necessity of Beauty has given me some sorely-needed hope.

Picking these three photographs didn’t require an exhaustive search through my files. All three are in my mind’s eye and in my heart. Of course, because I was trained to see by my art historian father and designer mother, and because I later became an art historian and then an art dealer, I can’t help but choose photos which meet my inner critic’s criteria for decent composition and palette and technical execution. But that’s just dotting my i’s and crossing my t’s. In all of my favorite photographs, two things come together for me. Sure, they must be something I can (usually begrudgingly) call a good photograph, but far more importantly, they must capture what is for me a great story. Each of these photographs take me back to the particular moment not only when I captured the image, but also when I saw what I had captured — which reflected back not just what I had seen, but what I needed to see, to learn, in order to move forward in my life. In order to heal.

The first one was taken in China, in the spring of 2013, where I had gone on a journey of forgiveness to the place where my mother spent the most formative and memorable years of her childhood. While I was there, I visited many different kinds of places of worship — Buddhist, Confucian, Taoist. This was taken at a Buddhist temple in Shanghai, the city in which my mother grew up. During my first four or five days in China, I was so busy that I didn’t have the time to look at the pictures I had taken. But when I finally did, I was stunned. I had taken hundreds of photographs of the same thing.

In China, there is a new generation that is called the Little Emperor Generation. Before they are old enough to go to school, these offspring of the Only One Child Edict are cared for by their grandparents, while their own parents work. The grandparents, according to many, coddle and spoil these children so much that they are disparagingly but sweetly called “little emperors”. But I didn’t know this when I was taking these pictures, and all I saw was LOVE! The love of people who were my parents' age when they were raising me. (My mother was 45 years old when I, her only child, was born. My father one month shy of 51.) Like the little emperors, I, too, was dressed to the tee and coddled and cared for, and like the little emperors my parents worked long hours. But unlike the little emperors, I had no grandparents. I had caregivers, and they were not my parents. So what I was photographing was people who were my parents’ age lavishing love and time and joy on these beautiful children. Although I took many of these photos, this one meant the most — because what I also learned in China was that, after so many years of not having been allowed to practice religion — many people were returning to these temples for the first time. Even more poignantly, these grandparents were being allowed to share their spiritual practices with their grandchildren in a way that has not been permitted with their own children. But the generation gap of this sharing created something extraordinary — a kind of freedom to improvise, to find new rituals, new meanings, new ways of accessing spirit. Wherever I went in China, no one said or did the same thing as anyone else when it came to rituals such as prayer, bowing, candle lighting or even pilgrimages. Memory met joy in the creation and sharing of new expressions of Spirit.

For me, who grew up with an older mother whose fear of “doing things wrong” meant that she was a by-the-book religious person who grew more rigid with each passing year, this photo was the envisioning I needed on my journey of forgiveness to China. An older person sharing a spiritual experience with their beloved in the most loving and freeing way. This is what I saw when I looked at this photo — and it is still a totem in the altar of my healing.

The next photo also captured a wonderfully healing moment for me. I had just landed at LAX on a trip that would also take me to New York, Kentucky, and Texas. I was in a crabby mood, and so I figured I would call on my tried-and-true joy practice, walking. Better yet, I would walk by the ocean in the city of my birth — Santa Monica. So I parked the car and downheartedly began walking north along a very crowded boardwalk. But when I rounded a corner, in the distance I saw the Santa Monica Pier. A place I always loved to go with my dad — who was a sucker for all piers, amusement parks and games of chance. The Santa Monica Pier had the trifecta. On the pier, there is still a small rollie coaster. When I saw it, I knew what I had to do — I had to go ride it. Riding rollie coasters was something my dad and I always did together. If anything was going to cheer me up, that would. And that’s when I saw him. This Buddhist monk, walking along the boardwalk, the rollie coaster behind him, talking on his cell phone. So I took his picture.

About ten minutes later, I was standing on the end of the pier looking out at the ocean, when I saw the same monk talking with two young women. I went over and told him that I had taken what I thought was a great photo of him. He was from Burma and the women, who hailed from various parts of the world, had been traveling with him. But when I showed him the photo, his face fell. “Oh,” he said with regret. “I was talking on the phone.”

I went on to have a wonderful chat with the young women, ride the rollie coaster, clear my mood, have a fantastic trip in LA and then on to New York, Kentucky, and Texas. But when I look at that picture, it was his remark that stuck with me.

I have tried to live a life without regrets, but I haven’t always succeeded. But in trying to make sense of the regrets I do have, I have found they have one thing in common -- not being present. And that, of course, is what that monk felt. Thich Nhat Hanh, of course, said it best:

“We can smile, breathe, walk, and eat our meals in a way that allows us to be in touch with the abundance of happiness that is available. We are very good at preparing to live, but not very good at living. We know how to sacrifice ten years for a diploma, and we are willing to work very hard to get a job, a car, a house, and so on. But we have difficulty remembering that we are alive in the present moment, the only moment there is for us to be alive. Every breath we take, every step we make, can be filled with peace, joy, and serenity. We need only to be awake, alive in the present moment.”

When I look at the photo of the monk on the beach with the rollie coaster, it reminds me that the beauty of that day for me WAS that I remained open to joy and present to my surroundings. It is a reminder to stay in the now -- to live a life of presence instead of ruing our regrets.

I took this picture on my fiftieth birthday trip to Costa Rica, where I stayed in the perfect little hermitage — at the top of 140 stairs with a panoramic view of the Pacific. It had no window panes, and many porches. It was hidden at the top of a hill and yet wide open to the world. It was perfect! Every morning I was awoken by the sounds of birds, and following those sounds with my eyes, I began to see the most gorgeous blue, green, red, black, blue, orange, yellow birds!!! It was glorious beyond words. A living prayer. A meditation on love. I took hundreds of pretty darn good pictures of amazing birds — the kinds of birds you usually see in nature publications. But of all those pictures, this is the one that sings to my soul.

Why? For someone who spends so much of her life in transit, I have a surprisingly difficult time leaving. Even if it is a trip I can’t wait to go on, the days before departure are always very very difficult for me. Fear, sorrow, and doubt always always assail me — and I believe all of their arguments! But what I always always forget is that the moment I drive away or the plane takes off, I feel such immense spiritual freedom and joy that my heart cracks open.

This picture is a perfect lesson for me. I could have seen it as a photo opportunity missed. But instead I see it for what it captures for me: The exquisite elation of departure.

Well, I certainly failed my own assignment. Three pictures and three paragraphs. HAH! Oh well. . .But it is probably time to wrap this all up.

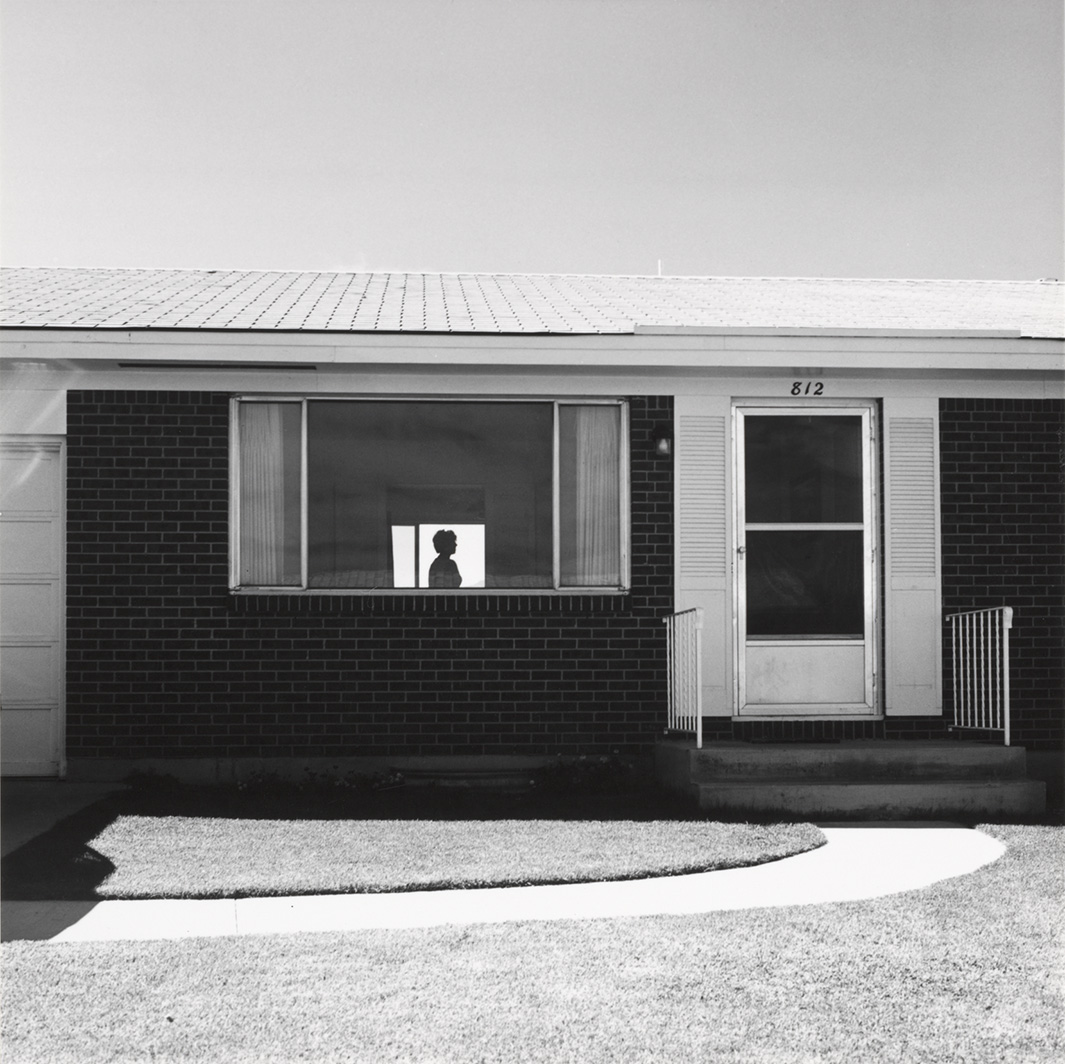

I have had the great good fortune of collecting, selling, and living with the work of many of the world's greatest photographers. But the one with whose ethos I most resonate is Robert Adams -- one of the great photographers of the West, of American life, of the deleterious effects of so-called human progress, and of the remaining hope of Nature. I love Adams' images, because they alway show me the stories I need to hear. Adams' words are as eloquent as his images. And so I will leave you with him -- a master teacher on my journey of learning how to see. And learning how to see is so critical at this tipping-point time on our planet. Because when we see, see from our hearts, see from our open and curious and awake minds, when we look deeply and truly pay attention, what we see is that we are all the same, all connected, all one people and one planet. This is the healing of sight.

“At our best and most fortunate we make pictures because of what stands before our camera, to honor what is greater and more interesting than we are. We never accomplish this perfectly, though in return we are given something perfect—a sense of inclusion. Our subject thus redefines us, and is part of the biography by which we want to be known.”