As I wrote in a recent blog, a few years ago I had the great honor of working with the incredible Susan Griffin on some memoir pieces — which ended up becoming an essay entitled “The Unholy Trinity of My Self-Loathing”.

This past spring, as I was sorting through my storage boxes trying to decide what to keep, toss, or sell, I found the photograph that I had written about in that essay. I had been looking for it for a while. Almost unthinkingly, I brought it with me. Last week, as I was settling into my little hermitage, it was on top of the first box I opened. I put it on the cafe table that serves as my makeshift desk, where I look at it every day.

A few days ago, listening, once again, to Angela Duckworth’s Grit, I found out why that particular photo was meant to accompany me on this journey: It’s because it’s time for me to release what happened the afternoon it was taken. More than that, actually. It is finally time for the Unholy Trinity of My Self-Loathing to be healed. That is the work I am meant to be doing this summer. Releasing that unhealthy life-limiting trifecta of old stories that have held me back from recognizing my True Self and realizing my purpose.

Here is what I have written about the moment captured in that photo:

It was a special treat to be picked up from school early and brought home to change out of my flannel grey uniform into my favorite dress, the white one with the blue, yellow, green and red pieces of fruit. For my mother, attending school was sacrosanct. I had started nursery school at two, Kindergarten a year later. I never missed a day for illness or family emergencies. So to be going to an art opening on a weekday afternoon meant something. . . and we were going because of me! My bright blue finger painting had been chosen to be in a show of paintings by kids from all over the city.

Perhaps I was acting excited, but more likely my mother had her speech rehearsed. Undoubtedly she and my father had discussed it, along with, I imagine, a joke or two about this being my Blue Period. Of course, I don’t know that this happened, but I can hear it in my mind as though it did—their well-matched, wry, wide-ranging intellectual humor and their well-meaning laughter at my expense.

My mother’s proclivity to worry and her need to moralize—the maternal desire to protect coupled with the British imperative for restraint and knowing one’s place—made this a teaching opportunity. One which, if passed up, might lead to further heartbreak for me. . .or worse, contribute to my becoming one of “those” children, the kind who took their privilege and place in the world for granted. I wonder what my dad said, whether he suggested that she not say anything at all, or, as he often did during their fights about my table manners or finicky eating, just deferred to her moral authority.

In the dressing room next to the high counter where my mother laid out my colored ribbons before brushing my hair back into the tight braid that always accompanied me out into the world, pulling my skin so taut that my eyelids seemed to stretch — truly not a hair out of place as though this were the one part of me she could even begin to try to tame — she knelt down and looked me in the eye: “You need to know that you were not chosen to be in this show because you have any talent as an artist. They chose your painting because they wanted dad to be there. It’s because your father and I don’t want you to get hurt later on that we need you to understand this now.”

I have no memory of feeling anything when she said this. And the photo of me taken an hour later standing next to my dubious monochromatic masterpiece does not depict a devastated child. There is no sadness in my eyes. But there is no particular joy either.

So, that begs the question: Why do I remember this moment so distinctly when so many other parts of my childhood have faded and blurred into the indistinct wallpaper that is the ongoing yet never urgent background to my adult existence? (Funny isn’t it, how whole years of our lives can get so easily erased from our ontological hard drives, but one seemingly inconsequential moment can become eternally etched into our psyches.) Moreover, why, when I have shared this story with others, have they heard it as so significant? Why have they always questioned me as to what I felt? And, most importantly, why haven’t I been able to answer?

To the world, my mother presented herself as creative, competent, controlled and unemotional, though I always felt the depths of her fear and had the perpetual urge to protect her. To this day, my brother and I (he, her stepson and twenty-two years older than I, but raised by her as a teenager) can never quite put a finger on the source of her immense power. But it was daunting. Her pronouncements felt like royal edicts—to question them seemed foolhardy. So, I took what she told me to be Truth.

But that’s not why that story has stayed with me. My mother often imparted her Great Truths. I heard them and filed them away for future use. The reason that story stayed with me is because I believed her. In my heart, I recognized that my painting was not special enough to have warranted being chosen on its own merit, just as I knew the moment she said it that of course it was my father they wanted and not me. I knew that dispassionately and clearly, even at four.

It’s not what or even how people impart things to us as children that create their lasting legacy in our psyches. It’s where those things come from in the people “teaching” us and, consequently, how those things land in us. The way that landing makes us feel weaves itself into the narrative tapestries of our lives.

Of course the adult me now knows that that is no way to talk to a child. I could rewrite that moment a hundred ways, most of which would have left out the conversation altogether. So I feel neither rancor nor animosity toward my mother, nor even much sadness toward some loss of innocence in myself. No. This is why it stuck: That afternoon, I was told that I was not good at the thing that the person I loved most in the world (my dad) valued and adored more than anything (art). Not only that, I learned that anyone — even me, in our gated 9,000-square-foot Spanish mansion with a world-famous father and a seemingly omnipotent mother — could be used as a pawn in the game called celebrity, a game I was just beginning to understand existed.

That moment was the beginning of the erosion of the illusion of my specialness, the moment when my childlike self-assurance born of privilege and enthusiasm felt undermined for the first time. So. . .good, right?! Partially, sure -- that illusion needed dissipating; I needed to see the man behind the curtain in the Oz called Hollywood. But what it also took away was the joy I felt in creation, replacing it with the desire to find something that would make me "good enough”. In that moment, I split -- I hid my heart and began following my head in trying to figure out what I might be able to do to become like my father.

That decision changed my life. Because for every one step forward in my creative life, two steps back have always followed. You see, when you grow up in fame, to achieve fame seems the only logical choice. Anything else would be failure. Admit it. When the kid of a famous actor becomes a plumber or even a cameraman, some part of you believes that kid didn’t “have what it took”. But what if that kid had EXACTLY what it took — to fix things or to capture images on film? That's not how we think, though, in this celebrity culture. So, if I wanted people to feel about me they way they felt about my dad, who was loved and lauded by everyone he met -- I reasoned with childlike logic -- I needed to find something I could genuinely be good at, as good as he seemed to be at all the things he did and knew and loved. And something, no, not something—the most important thing to the most important person in my life—had been ticked off the list.

That is what I wrote two years ago — as I began to excavate the three childhood incidents that formed the Unholy Trinity of My Self-Loathing.

This is the photograph I brought with me — of me and my “dubious masterpiece”.

(As I have looked at it this week, I noticed something I had never seen before. Though my large green ribbon blocks the full title to my “painting”, I am pretty darn sure it is “Blue Period”. Which is EXACTLY the title my mother would have chosen — to humorously indicate that my art-savvy parents knew this was not really any “good”!)

So, this is what I heard Angela Duckworth explicate a few evenings ago, which made me understand why that photo came with me, why I have been looking so intently at that little girl on my desk all week, and why I need this to write this as my Independence Weekend post.

In her chapter on Hope, Duckworth talks about how teachers and parents help or hinder children learn — by choosing a growth mindset or a fixed mindset. As children, if we are told that we can never be good enough at something (fixed mindset), we take that in as carved in stone. Some part of us gives up on that quality in ourselves. Whereas, if we are encouraged to believe that we can improve at something -- the growth mindset -- we continue to persevere and practice. What was particularly striking to me -- as someone who has struggled to tamp down some very nasty voices in her head -- was Duckworth's assertion that a growth mindset can lead to much more optimistic self talk. And we all know how much easier it is to achieve our goals when we are our own rooting section, as opposed to the ones laying out the trip wires for our predicted fall.

A few years after this photo, in one of the after-school art classes I continued to take, I was painting a small oil of a dog inspired, I’m pretty sure, by the TV show, Please Don’t Eat the Daisies. I could NOT get the painting to turn out the way I saw it in my head — so finally I had to ask the teacher, Mrs. Davis, to help me finish it. I watched as she turned the expressionless blob that had been the face into a sweet dog visage. In that moment, I realized with utter certainly that what I saw in my mind would NEVER come out of my hand. It was one of the defining moments of my childhood. (Interestingly, I do not have any of the pieces of art I created throughout my childhood — I always continued to draw, almost obsessively — but I have always kept that little oil painting.)

Here it is.

The way in which we see ourselves as learners and later as individuals — through the lens of the growth or fixed model inculcated in us as children — determines not only our grit (which Duckworth defines as having the perseverance and passion for achieving our longterm goals) but also, I believe, our joy. Because if we are told that there is something we cannot do, we are robbed — in the moment we believe them — not only of our present joy, but also of all our future joy in that endeavor.

When I accepted my mother’s statement, not only my belief that I could become an artist, but also my joy in trying was eroded. Recently I took a pottery class. It was something I had wanted to do for years. I was horrendous at it. So I quit. In other areas of my life, however, horrendous has never been a deterrent. It took me seven years to go from a 3.5 to a 4.0 tennis player — even after seasons where I won over 90% of my matches! I knew what the problem was: I cared more about winning for the team than I did about having fun and playing well. Every year my teammates moved up a rank. Every year I did not. And the next year I would form a team and try again. I knew I could become a 4.0, and I wasn’t about to stop trying. Finally, it all came together. I put together a 4.0 team, played every match with as much joy as I could muster. . .and at the end of the season, I was moved up to 4.0. Finally!

Why did I stick with tennis (and many other passionate pursuits like horseback riding), but not with art? My parents were what Duckworth would call “paragons of grit”. And in almost every other area of my life, they passed their grit onto me. It was in the places in their own lives where they carried the burden of fear that they did not encourage me — and those three areas were money, art, and privilege. Both always feared that the next job, the next film or creative project, could be their last and that the blessings of their lives must be earned through humility and hard work or they would be taken away. And both valued art/design more than anything in the world while themselves feeling unworthy and untalented as artists. We pass on what we have not healed. Their fears as they were transmitted to me created My Unholy Trinity of My Self-Loathing.

It has taken me quite a while to scrape the residue of that fixed teaching about art off the other creative areas of my life. I'm still doing it! But it has been this Daily Practice of Joy and the sharing of it with you that has been my biggest breakthrough in dissolving some of the tenaciously sticky ooze of my shame. And it's some pretty gnarly old shame.

After college, I was accepted into grad school at one of the most prestigious acting programs in the country. That summer, I came back to LA, where I worked two jobs while spending what remained of my free time with my dad working on a book of essays. One day out of the blue, he turned to me and said, “You are such a talented writer. I read the one-woman show you wrote. I wish you would keep writing instead of going into acting.”

I don’t remember what I said to him, but I do remember what I felt. I was pissed off and hurt. My dad had come to see me in one play my entire life. One. My senior year of high school. And when he and my stepmother showed up, you would have thought the royal family had arrived. That one-woman show he mentioned that I wrote, I also acted in and directed my last year in college. He didn’t come to see that or any of the many other productions in which I had starred.

When I got into a grad school that had admitted only four women out of the thousand who had auditioned, it affirmed for me what my own father never had. I wore my grad school acceptances as a badge of honor.

So that summer, from that old place of hurt and anger, I could not hear my dad’s words of praise for my writing. Instead I heard: Don’t go into acting. It’s a difficult life. You’re not cut out for it. You’re not good enough. Then, out came the four R’s that have been the mainstay of my my life: I Resented, Resisted, Rebelled, and Reacted against what he said. Because when I decided I couldn’t be an artist, I set my sights on becoming an actress. And I was good. I was really good. That is to say, I had all the skills. What I didn’t have was the grit.

Of course, my dad knew me about as well as anyone has ever known me. And sure enough, after a semester of grad school, I saw with absolute clarity that, talent or no, acting was not for me. All my classmates had the passion for acting. They were willing to suffer for their art. I was not. At least not that art. So I dropped out.

Grit, Duckworth avers, entails Interest Practice Purpose and Hope. I had the first three. I have had the first three in almost everything I have done creatively. What I lost when I was four was the hope.

Or so I thought.

From the time I quit grad school in acting, I began to write. And I wrote and wrote and wrote. I wrote my way through a doctoral program, and then got jobs that allowed me to write in every spare moment I had. Eventually I wrote my father’s biography, I wrote for television, and I even wrote articles in magazines, journals and newspapers I had long admired. Despite all that, I never had the courage to call myself a writer. Writing being an “art”, of course -- and how could I call myself an artist? When I read things I had written, I tore them apart. Faulkner famously said, "In writing, you must be willing to kill all your darlings." No problem for me! I slaughtered them mercilessly, and then pummeled myself good and hard, too, while I was at it.

Without hope, the "not good enough" voice always trumped whatever successes I had. And that led where it could only lead -- to self-loathing. To keep giving up on the something I valued so much (my belief in my own creativity) has been all the fertilizer that the seeds of self-loathing sowed by my mother (who had her own bumper crop to contend with) needed. Every time I did not have the grit I needed to follow my heart and be the writer I wanted to be — I felt as though I had failed myself.

Over the years, all the people who encouraged me to write — my best friend who bought me my first computer, the teachers and writers who had taken the time to offer constructive criticism and praise, my friends who have been gracious and supportive readers — sure, I heard them. . .but their words got stuck in the mire of my self-loathing. Even after writing a book that got only good reviews and appearing on talk shows and prestigious radio programs, I chalked it up to it being “because of dad”. . .just like my mother told me it would be.

But still I wrote. I couldn’t not write. You see, I have been a voracious reader my whole life. I felt about words the way my father felt about art. But, as he did with artists, I idolized writers and feared I could never match their genius. Even despite that, I couldn’t stop writing. But it wasn’t until listening to Duckworth that I understood why the grit I do have has helped me persevere in the belief that I can override my self-loathing. Why, ultimately, I never gave up on myself.

I should digress a moment and share why I’m reading Grit in the first place. It’s not actually the kind of book toward which I always gravitate. I bought it it because my friend Pat said that when she read it, she thought of me. How despite all of the setbacks and shitstorms I have faced in the time she has known me, I have never stopped pursuing my dream of building a creative spiritual life that gives back and contributes something to the world. She reminded me that, through thick or thin, no matter what, my spiritual practice has been my mainstay. And, for as long as I can remember, reading, writing and seeing have been the core of my spiritual practice. Which is to say, for as long as I can remember, I have been reading, writing, and seeing myself whole.

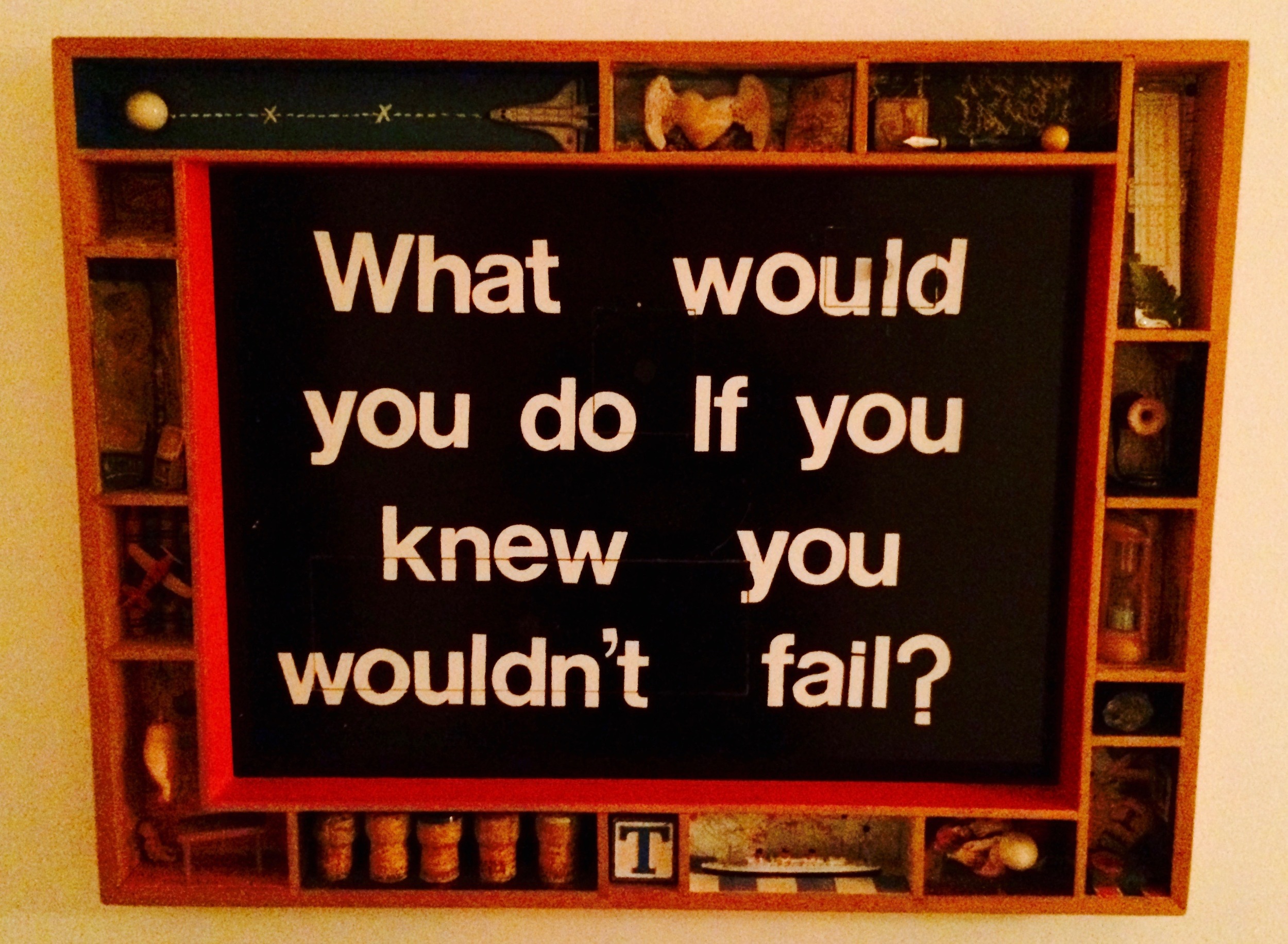

This is the first thing you see when you walk into my friends Jane and Tess' house:

When I saw that, I didn't even need to think about my answer. What would I do if I KNEW I couldn't fail? Heal. My spiritual practice has always been learning to heal myself so I could help others learn to heal themselves.

When I first started reading Duckworth's book, all I could see were the ways I didn't have grit. But the more I listened to the components of grit, the more clues I got to understanding my own history. Then the other day, the light bulb went off. I thought, even if humanly we do not have all the grit components we may need, if we believe in something bigger than our human wills to get us through, then we can access all the grit we need -- spiritually. And what I have always believed (even though I was sometimes afraid I might be the asterisk, the one exception to this rule) is that we ALL carry within us every spiritual quality there is. We are the rays of a Sun that supplies us all the light and energy and warmth and life we need. Sometimes, however, we get our heads so stuck in the clouds of our human histories that not only can we not see that Sun, but we completely forget that as the rays, we have already shone through the clouds.

Pat’s right. I have grit. Always have. I have survived, more than survived even, things that would have flattened other people. But why? Not because I am an extraordinarily gritty human being. On the grit scale, I would give myself a lifetime B/B-. Rather because, each time I have been steamrolled, I have know there is only one place to turn — and that is to my Higher Power, not out there somewhere, but already in me!!

Which is why I am writing this as my Independence Day blog. Because it is time, here and now, to declare my independence from those old stories. I am finally ready!! And it is because of this blog, the book I am writing, and showing up every day to do the hard work -- all while believing in a Power much bigger than my puny and deeply unreliable human will. And the X Factor in all of this? You guessed it: Joy. The reason creating and writing about a Daily Practice of Joy has changed my life is because Joy has been both the connector between my overactive head and my under-encouraged heart on the human plane, as well as the barometer of my awareness of my connection to Spirit.

Courage, as Brene Brown courageously reminds us in so much of her work, stems from the French word coeur — heart. By creating this blog, I finally gave myself permission to find true enJOYment in writing and in sharing my words, and even allowing myself to post the photographs I have loved taking for decades (the photographs that teach me how to see and what brings me joy). Finding this joy has allowed me to connect a lot of dots -- all the parts of me to all the parts of you, of nature, of the planet. This newfound courage to create in the ways I have always longed to brought my joy-based spiritual practice of reading, writing and seeing myself whole into alignment with the grit with which my parents instilled me -- resulting in the trifecta. . .three words all based on the same root word. Three words that lead to the same place: Whole, Holy, Healing.

During Picasso’s famous Blue Period, he used an almost monochromatic palette of blues to depict the misery of the human condition. Wanna know what came after the Blue Period? Because Picasso, let’s face it, knew a thing or two about change. What came after the Blue Period was the Rose Period. What makes rose? Red and white!

And so today — I bid adieu to my all-too-lengthy Blue Period and finally declare my Independence therefrom. I happily don my joyous rose-colored classes as I hold out my hand to all of you, who have joined me on your own journeys back to joy!

Doing the work of deep excavation ain’t easy. And sometimes it ain’t quick either. . .I’ve been chewing this cud for a very very long time. But Mr. Jefferson was oh so right: There comes a time in the course of human events when it absolutely becomes necessary for us to dissolve the bands that have bound us to the stories from our past that we no longer need.

This weekend, as we celebrate our Independence Day, I encourage you ask yourself: From what life-limiting narratives are you ready to declare your freedom? Whatever they are, I support you. Because we are on this journey together — and I am so grateful that we are. It is time for us all to stop listening to old tapes, dancing to long-forgotten tunes, hearing the voices of well-meaning people who struggled with their own old tapes and long-forgotten tunes -- and begin to step into JOY!

Let Freedom Ring!