My favorite poem in my early twenties was written by Audre Lorde. It is called Portrait, and I used it as the invocation for a one-woman show, which I wrote and performed, about Lillian Hellman, Dorothy Parker, and Edna St. Vincent Millay.

Portrait

Strong women

know the taste

of their own hatred

I must always be

building nests

in a windy place

I want the safety of oblique numbers

that do not include me

a beautiful woman

with ugly moments

secret and patient

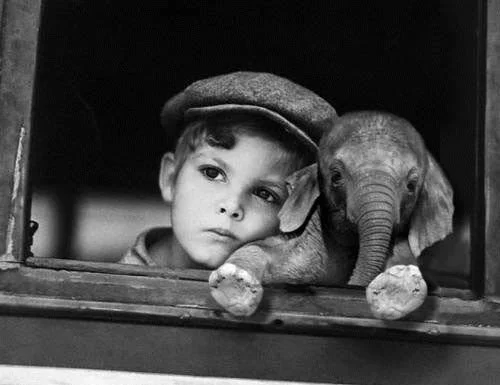

as the amused and ponderous elephants

catering to Hannibal’s ambition

as they swayed on their own way

home.

Although I picked the poem because it described each of the women in my show, it became a kind of credo for me. The first time I read it, I felt a bittersweet pang of recognition. I had never heard a woman describe herself as both strong and self-hating. It captured my own contradictions. It was a revelation.

Reflected back to me were my own coping mechanisms — seeking home in stormy places, wanting the anonymous comfort of a crowd to assuage my lifelong loneliness. But really, it was all about the elephants! Secret and patient. Amused and ponderous. There I was again — or there I hoped to be. What I loved most? That they were “catering” to Hannibal’s ambition as they swayed on their own way home. Those elephants made me hope, trust, have faith in some way beyond words, that whatever choices we strong women who struggle with our inner demons may find ourselves making to cater to society’s dictates or to other people to whom we cede our power, we will, eventually, find our own way home.

I have never stopped loving this poem, nor have I stopped admiring the strong self-hating woman who inspired me to write my play — Lillian Hellman.

I fell in love with Lillian Hellman when I was a teenager after reading what she said to the McCarthy and his henchmen on the House Un-American Activities Committee, when they accused her of being a Communist. Upon being asked to name other supposed Communists, Hellman refused, saying, “I will not cut my conscience to fit this year’s fashions.”

I became obsessed with the McCarthy era when I was fifteen years old, after studying it in AP US History and realizing that the president of our student council, of which I was a member, was the daughter of one of McCarthy’s two main allies. Her dad’s photo was in our history book. That personal connection to an era that had long fascinated me blew my teenage mind: The idea that a period of time when people’s lives had been torn apart could become “history”, and the “evil” people from the past could go on to live in anonymity raising children who weren’t monsters, shook up all my childhood ideas of good and evil, right and wrong, justice and retribution.

I decided to ask my dad about it. He told me that he had been greylisted at the time, which meant that his name was put on a list of purported Communist sympathizers, who the movie studios were told not to hire. He said it was the hardest thing he had ever gone through, not just the fact that he was unable to work and scared for his livelihood and future, but watching his friends be driven out of the country or even to suicide.

He told me that he had called on some connections through the Los Angeles art world and had been able to have his name cleared by the FBI. But his fear from that time remained palpable for the rest of his life. When I was in my early twenties, I worked for a left-wing organization and, as a result, I was invited to an anti-Apartheid gathering honoring Bishop Tutu. I was so excited to hear such a great man speak, but my dad’s only comment was, “Be careful you don’t get on any lists that can come back and cause you trouble you later.”

After my dad died, one of the last things I found when I cleaned out his house was a very old manila envelope in the utility closet hidden behind the air conditioning unit. In it were the FBI documents that had cleared him with HUAC. I read through them, and as I did, my hands began to shake. It was a lengthy document, in which he agreed to many many things I know he did not believe. Most notably, he said, “I believe that anyone who pleads the Fifth is unAmerican.”

The next day I was scheduled to have lunch with my dear dear Uncle Eddie. Not my real uncle, Eddie Albert had always acted as my surrogate dad when my own dad was out of town — at school and other events. He was one of the most joyful loving people I have ever known — only surpassed by his wife, Margo, who was the single most joyful and light-filled person I think I have ever met. They were one of the great blessings of my childhood.

At lunch, I shared with Uncle Eddie how disturbed I was after reading this document. How could my father have agreed to such a thing?

I will never forget his response. The face of that man who always had a smile for me, who laughed at instead of scolded me for my childhood foibles, clouded over into a deep stormy rage. He literally pointed his finger at me and said with such deep anger, “Don’t you EVER! Don’t you EVER judge the actions of another person unless you’ve been in their shoes!”

He proceeded to tell me the stories of all of their friends whose lives and careers had been ruined, who had fled the country, who had killed themselves. Then, in a very quiet voice, he told me something I had never known. He told me that Aunt Margo — my Aunt Margo, that pure loving delight of a woman — had been blacklisted and had never worked again. Margo went on to help found Plaza de la Raza in Los Angeles (she had grown up in Mexico before coming to the United States as a singer, dancer, and later actress), which was an incredible cultural center for the Latino community. It became the outlet for all of her thwarted creativity and for her desire to help others who had been disenfranchised in their own way. As no one had been able to help her.

I will never ever forget that afternoon with Uncle Eddie. It was the afternoon where I understood that history can never be understood by the reader, and that the actions of those who came before must never be judged by those who follow behind. It was the afternoon where the consequences of speaking or not speaking one’s truth came home to me in a deeply profound and life-changing way.

This past year, I have discovered another poem that has become a lifeline. It’s by William Stafford:

Following the Wrong Gods Home

If you don't know the kind of person I am

and I don't know the kind of person you are

a pattern that others made may prevail in the world

and following the wrong god home we may miss our star.

For there is many a small betrayal in the mind,

a shrug that lets the fragile sequence break

sending with shouts the horrible errors of childhood

storming out to play through the broken dyke.

And as elephants parade holding each elephant's tail,

but if one wanders the circus won't find the park,

I call it cruel and maybe the root of all cruelty

to know what occurs but not recognize the fact.

And so I appeal to a voice, to something shadowy,

a remote important region in all who talk:

though we could fool each other, we should consider--

lest the parade of our mutual life get lost in the dark.

For it is important that awake people be awake,

or a breaking line may discourage them back to sleep;

the signals we give--yes or no, or maybe--

should be clear: the darkness around us is deep.

As I wrote last week, recently I have exhumed something very deep and old — my fear of speaking my truth to others, and my deafness to the truth that speaks to me.

I have been following the wrong god home for most of my adult life — the god of head not heart, the god of contraction not expansion, the god of work not joy, the god of societal expectations instead of spiritual inspiration. The god of fear not Love.

I have always thought myself an iconoclast, and never minded that my life did not mold itself to a norm to which I never aspired. But I see now that in perhaps the most significant of ways, I have conformed — I have hooked my trunk to the tail of the elephant before me, and I have missed my circus! In not speaking my truth, in not listening to what makes me feel alive, but rather shaping my words to the pleasures of others to assuage my own fears of never being loved, I have stopped loving myself.

I know I’m not alone in this. For this planet to survive the gradual numbing to which we all succumb as a refuge from the feelings that overwhelm us, we have to keep acknowledging that shadowy voice in each of us that is begging to be released.

For it is vital that awake people be awake, and we must have the courage to speak — be it yes, no, or maybe.

This past week, as I have begun to recognize this lifelong pattern, I have been wracked with terror — palpable anxiety and a fear that surface in ways utterly disproportionate to the situation at hand — a question asked, a text received, a voicemail heard. My heart beats out of my chest and my adrenaline courses like plutonium through my whole body. I’ve sat with it and sat with it and sat with it, witnessing it, trying to feel what it underneath it all.

I found my answer in an article about Ken Wilber called “Speaking Your Truth”, in which he writes that, unless we speak our truths, we will always suffer from our silences. We will rarely be loved or lauded for our truths, but once we know them, we cannot succumb to the lure of invisibility or timidity, or we will pay the consequences. He closes this incredible essay with a very hopeful quote, by — of course! — Audre Lorde:

“The speaking will get easier and easier. And you will find you have fallen in love with your own vision, which you may never have realized you had. And you will lose some friends and lovers, and realize you don’t miss them. And new ones will find and cherish you. . .And at last you’ll know with surpassing certainly that only one thing is more frightening than speaking your truth. And that is not speaking.”

In junior high, I had a teacher I adored named Sally Jordan. She was one tough broad, with big opinions about everything. She called me the Bad Penny, and loved my rebellious creatively weird approach to life and academics. She let me write epic poetry and cast me as the lead in Shakespeare plays. She never judged the fact that half my belongings ended up in the Lost & Found. She saw me as a creative spirit— and reflected back to me that who I was was all right with her!

When she asked us to pick a quote for our yearbook pages that captured the essence of who we were, I searched and searched for a quote that the thirteen-year-old me could hold up to Mrs Jordan’s standards. This is what I chose:

“Forge thy tongue on an anvil of truth and what flies up, though it be but a spark, will have light.” - Pindar

Upon reading my quote in the yearbook, my friends teased me that it made their tongue hurt. No one seemed to “get” it, and that’s what I remember about it. In fact, it wasn’t until this week that it popped into my head again. I re-read it. Wow!

When we speak our truth — even just a spark of it — it will have light.

To begin to speak my truth after a lifetime of unconscious lying has felt seismic. All week long, I have thought of Kaspar Hauser, the German boy in the early 19th century who was discovered as a teenager after having been kept prisoner his whole life in a dark basement eating scraps of bread with water. When he was brought out into the real world, everyone assumed that he would be so grateful to have been released from his prison — to meet people, to see nature, to have friends, to eat real food. But Kaspar couldn’t take it. After a little while, it was all too much — and he returned by choice to the darkness and the meager existence he had previously lived.

Changing our lifelong conditioning — whatever it may be — can feel like the hardest thing we have ever been asked to do. And even though we know we are being led out of the darkness, even though we can see sparks of light illuminating our souls, the old darkness can feel so comfortable, so familiar, so seductive.

How do we stick with it? How do we change what we know we need to change to live our brave lives, to save our souls, to speak our truths?

Every time we doubt our truths in favor of other people’s or society’s opinions, we step back into the shadowy comfort of our familiar dark basements. And these days, let’s face it, we can fool ourselves much more easily into thinking those dark basements are where we most want to be. After all, diversions can be delivered in just two days and distractions come on demand.

But once again, here come the elephants to poetically remind us of our truths.

For as long as I can remember, one of the great joys in my life has been poetry. Once again, I owe it to my dad, who clearly knew what he was doing when he paid me a buck for every poem or Shakespearean soliloquy I learned by heart and recited to him. Mercenary motives may have got me in the door, but the way the lyrical words I was learning danced in my mind and off my tongue, the visions of delight or understanding of sadness they brought, became a lifelong lifeline. Poetry is a huge part of my daily practice of joy.

How do we find the courage to begin to heal our pasts, to speak our truths, to step into the light and shine, shine, shine? Well, the same way you get to Carnegie Hall — practice.

This past month has been one of the hardest months of my life — and I’ve had a lot of difficult months in my life! But the practices I have consciously put in place — finding joy every single day, spiritual journaling, connecting with the people who love me, witnessing instead of reacting, reading inspirational words, driving and hiking, watching the birds, conscious gratitude — these practices have allowed me to see that I am exactly where I need to be.

So, here are the poetic elephants that brought me back full circle to the truth that can never be taken away . . . from any of us. I'll let Hafiz take it from here. . .

You are the sun in drag.

You are God hiding from yourself.

Remove all the “mine”—that is the veil.

Why ever worry about

Anything?

Listen to what your friend Hafiz

Knows for certain:

The appearance of this world

Is a Magi’s brilliant trick, though its affairs are

Nothing into nothing.

You are a divine elephant with amnesia

Trying to live in an ant

Hole.

Sweetheart, O sweetheart

You are God in

Drag!